Shoghi Effendi

Shoghi Effendi | |

|---|---|

شوقی افندی | |

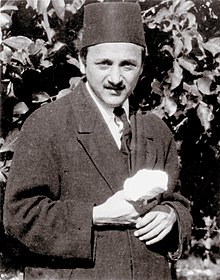

Effendi in Haifa, 1921 | |

| In office 1921–1957 | |

| Preceded by | ʻAbdu'l-Bahá |

| Succeeded by | Universal House of Justice |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Shoghí Rabbání 1 March 1897 Acre, Ottoman Empire (now Israel) |

| Died | 4 November 1957 (aged 60) |

| Resting place | New Southgate Cemetery, London 51°37′26″N 0°08′39″W / 51.6240°N 0.1441°W |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Spouse | |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (grandfather) Baháʼu'lláh (great-grandfather) |

| Signature |  |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Baháʼí Faith |

| Lineage | Afnán (see: § Ancestry) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

Shoghí Effendi (/ˈʃoʊɡiː ɛˈfɛndi/;[a] Persian: شوقی افندی;1896 or 1897[b] – 4 November 1957) was Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith from 1922 until his death in 1957.[3] As the grandson and successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, he was responsible for creating a series of teaching plans that oversaw the expansion of the Baháʼí Faith to a number of new countries, and also translated many of the written works of crucial Baháʼí leaders. Upon his death in 1957 leadership passed to the Hands of the Cause, and in 1963 the Baháʼís of the world elected the Universal House of Justice, an institution which had been described and planned by Baháʼu’llah.[4]

Effendi, an Afnán, was born Shoghí Rabbání[c] in ʻAkká (Acre) where he spent his early life,[5] but later went on to study in Haifa and Beirut, gaining an arts degree from the Syrian Protestant College in 1918 and then serving as ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's secretary and translator. In 1920, he attended Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied political science and economics, but before completing his studies news reached him of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's death, requiring him to return to Haifa. Shortly after his return at the end of December 1921 he learned that in his Will and Testament ʻAbdu'l-Bahá' had named him as the Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith.[6]Shoghi Effendi’s clear vision for the Baháʼí Faith's progress was inherited from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and based on the original writings of Baháʼu’llah, two particularly important aspects of his leadership focused on building its administration and spreading the faith worldwide.[7]

During his 36 years as Guardian Shoghi Effendi translated and expounded on many of the writings of Bahá’u’lláh and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, established plans by which the faith was enabled to spread globally,[8] and sent more than 17,500 letters. He kept in touch with progress in all existing Bahá’i communities as well as monitoring and responding to the situation in the Middle East, where the believers were still suffering persecution. He also began work on establishing Haifa, Israel, as the Bahá’i World Center, and created an International Bahá’i Council to aid him in his work, several members being newly appointed Hands of the Cause. He also presided over the community's enlargement from 1,034 localities in 1935 to 2,700 in 1953, and further to 14,437 localities in 1963. From the beginning to the end of his leadership, the total population of Baháʼís around the world grew from 100,000 to 400,000.[9]

Shoghi Effendi passed away during a visit to London in 1957, having contracted Asian flu,[10]and is buried at New Southgate Cemetery in the city of London.[11]

Background

[edit]

Born in ʻAkká in the Acre Sanjak of the Ottoman Empire in 1896 or 1897, Shoghi Effendi was related to the Báb through his father, Mírzá Hádí Shírází, and to Baháʼu'lláh through his mother, Ḍíyáʼíyyih Khánum, the eldest daughter of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[12] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, who provided much of his initial training, greatly influenced Shoghi Effendi from the early years of his life. Shoghi Effendi learned prayers from his grandfather, who encouraged him to chant. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also insisted that people address the child as "Shoghi Effendi", ("Effendi" signifies "Sir"), rather than simply as "Shoghi", as a mark of respect towards him.[13]

As a child Shoghi Effendi was aware of the difficulties endured by the Baháʼís in ʻAkká, which included attacks by Mírzá Muhammad ʻAlí against ʻAbdu’l-Bahá. Mirza Muhammad-‘Ali, who was ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s younger half-brother, and who was aggrieved at ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s designation as Baháʼu’llah’s successor, began plotting to discredit him by falsely making it known that he was the cause of the uprising in Ottoman Syria. The problems which this caused in the Baháʼí community were felt as far away as Iran and beyond.[14] As a young boy, he was aware of the desire of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (reigned 1876–1909) to banish ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to the deserts of North Africa, where he was expected to perish.[13]

Tablet from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

[edit]Being ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's eldest grandson, the first son of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's eldest daughter Ḍíyáʼíyyih Khánum, Shoghi Effendi had a special relationship with his grandfather. Zia Baghdadi, a contemporary Baháʼí, relates that when Shoghi Effendi was only five years of age, he pestered his grandfather to write a tablet for him, which ʻAbdu'l-Bahá obliged:

He is God! O My Shoghi, I have no time to talk, leave me alone! You said write, I have written. What else should be done? Now is not the time for you to read and write. It is the time for jumping about and chanting O My God! Therefore, memorize the prayers of the Blessed Beauty and chant them that I may hear them. Because there is no time for anything else.[15]

Shoghi Effendi then set out to memorize a number of prayers, and chanted them as loud as he could. This caused family members to ask ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to quieten him down, a request which he apparently refused.[15]

Education

[edit]Shoghi Effendi’s early education took place at home with other children from the household, and was taken care of by private tutors who gave him instruction in Arabic, Persian, French, English, and literature. From 1907 to 1909 he attended the Jesuit institution College des Freres, a Jesuit institution in Haifa, where he studied Arabic, Turkish, French and English. In 1910, during the time that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was residing in Egypt prior to his journeys to the West Shoghi Effendi was briefly enrolled in the College des Freres in Ramleh. Plans for him to accompany his grandfather on his travels fell through when the port authorities in Naples prevented him from continuing, ostensibly due to health issues. On his return to Egypt sometime after March 1912 he was sent to a Jesuit boarding school in Beirut, transferring in October to the preparatory school attached to the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut, graduating in 1913. Later that year Shoghi Effendi returned to the Syrian Protestant College as an undergraduate, achieving a BA in 1917, but despite enrolling there as a graduate student, he returned to Haifa without completing his degree. During his time at the Syrian Protestant College he spent his visits home to Haifa assisting ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in translation, becoming his full time secretary and translator from the end of 1918.

By the spring of 1919 the intensity of Shoghi Effendi’s secretarial work had taken its toll on his health, resulting in recurring occurrences of malaria, and by the spring of 1920 he was so unwell that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arranged for him to convalesce at a sanatorium in Paris. Following his recovery he enrolled in the Non-Collegiate Delegacy at Balliol College, Oxford, in order to improve his English translation skills.[16]

Death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

[edit]While Shoghi Effendi was studying in England he learned of the passing of ʻAbdu’l-Bahá during the early hours of 28th November 1921, news which came as a grievous shock since he had been unaware that his grandfather was ill.[17] Following his return to Haifa on 29th December 1921 the prerequisites of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Will and Testament were announced, unequivocally stating that Shoghi Effendi was to be appointed as ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's successor and Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith[18].[19] The institution of the Guardianship had been conceived by Baháʼu’llah, with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá outlining its specific functions and jurisdiction in his Will and Testament, two particularly important functions being the interpretation of the Baháʼí teachings and guiding the Baháʼí community.[20]

Private life and marriage

[edit]Shoghi Effendi's personal life was largely subordinate to his work as Guardian,[21] and it wasn’t until 1950 that he was able to secure the secretarial support he required in order to deal with mounting correspondence. By then he had established a timetable involving continuous hard work when he was in Haifa, with breaks during the summer during which he spent time in Europe, initially in the Swiss Alps, traversing Africa from south to north in 1929 and 1940. In 1937 he married Mary Maxwell, daughter of the Canadian architect William Sutherland Maxwell and May Maxwell, conferring on her the name Rúhíyyih Khánum. Shoghi Effendi had first met Mary in 1923 when she went on pilgrimage with her mother, and it was during a third pilgrimage in 1937 that Shoghi Effendi asked her mother for her daughter’s hand in marriage. The marriage took place in Haifa on 25 March 1937, in the room of Bahíyyih Khánum in the House of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Following the ceremony a cable was sent to America, stating, "Announce Assemblies celebration marriage beloved Guardian. Inestimable honour conferred upon handmaid of Baháʼu'lláh Ruhiyyih Khanum Miss Mary Maxwell. Union of East and West proclaimed by Baháʼí Faith cemented. Ziaiyyih mother of Guardian."[22] Rúhíyyih Khánum, as she was now known, was to become not only his wife but also his lifelong assistant in his work.[23] Shoghi Effendi held Iranian (Persian) nationality throughout his life and travelled on an Iranian passport, although he never visited Iran.[5]

Administration

[edit]The Baháʼí community was relatively small and undeveloped when he assumed leadership of the religion, and he strengthened and developed it over many years to support the administrative structure envisioned by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Under Shoghi Effendi's direction, National Spiritual Assemblies were formed and many thousands of Local Spiritual Assemblies were created. He coordinated plans and resources to raise several of the continental Baháʼí Houses of Worship around the world; construction of which continued into the 1950s.[24]

Starting in the late 1940s, after the establishment of the State of Israel, he started to develop the Baháʼí World Centre in Haifa, including the construction of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, the International Archives, and the gardens at the Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh.

In 1951 he appointed the International Baháʼí Council to act as a precursor to the Universal House of Justice, and appointed 32 living Hands of the Cause — the highest rank of service available, whose main function was to propagate and protect the religion.[24]

Growth

[edit]From the time of his appointment as Guardian until his death the Baháʼí Faith grew from 100,000 to 400,000 members, capitalizing on prior growth and setting the stage for more. The countries and territories in which Baháʼís had representation went from 35 to 250.[25] As Guardian and head of the religion, Shoghi Effendi communicated his vision to the Baháʼís of the world through his numerous letters and his meetings with pilgrims to Palestine.[24]

Starting in 1937, he set into motion a series of systematic plans to establish Baháʼí communities in all countries.[24] A Ten Year Crusade was carried out from 1953 to 1963 with ambitious goals for expansion into almost every country and territory of the world.

Other

[edit]In a more secular cause, prior to World War II he supported the work of restoration-forester Richard St. Barbe Baker to reforest Palestine, introducing him to religious leaders from the major faiths of the region, from whom backing was secured for reforestation.[26]

Leadership style

[edit]As a young student of twenty-four, Shoghi Effendi was initially shocked at the appointment as Guardian. He was also mourning the death of his grandfather to whom he had great attachment. The trauma of this culminated in him making retreats to the Swiss Alps. However, despite his youth, Shoghi Effendi had a clear idea of the goal he had for the religion.[24] Oxford educated and Western in his style of dress, Shoghi Effendi was a stark contrast to his grandfather ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. He distanced himself from the local clergy and notability, and travelled little to visit Baháʼís unlike his grandfather. Correspondence and pilgrims were the way that Shoghi Effendi conveyed his messages. His talks are the subject to a great number of "pilgrim notes".

He also was concerned with matters dealing with Baháʼí belief and practice — as Guardian he was empowered to interpret the writings of Baháʼu'lláh and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, and these were authoritative and binding, as specified in ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's will.[24][27] His leadership style was however, quite different from that of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, in that he signed his letters to the Baháʼís as "your true brother",[28] and he did not refer to his own personal role, but instead to the institution of the guardianship.[24] He requested that he be referred in letters and verbal addresses always as Shoghi Effendi, as opposed to any other appellation.[citation needed] He also distanced himself as a local notable.[24] He was critical of the Baháʼís referring to him as a holy personage, asking them not to celebrate his birthday or have his picture on display.[24]

Translations and writings

[edit]

In his lifetime, Shoghi Effendi translated into English many of the writings of the Báb, Baháʼu'lláh and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, including the Hidden Words in 1929, the Kitáb-i-Íqán in 1931, Gleanings in 1935 and Epistle to the Son of the Wolf in 1941.[24] He also translated such historical texts as The Dawn-Breakers.[24] His significance is not just that of a translator, but also that of the designated and authoritative interpreter of the Baháʼí writings. His translations, therefore, are a guideline for all future translations of the Baháʼí writings.

The vast majority of his writings were in the style of letters to Baháʼís from all parts of the globe. These letters, of which 17,500 have been collected thus far,[24] are believed to number a total of 34,000 unique works.[29] They ranged from routine correspondence regarding the affairs of Baháʼís around the world to lengthy letters to the Baháʼís of the world addressing specific themes. Some of his longer letters and collections of letters include World Order of Baháʼu'lláh, Advent of Divine Justice, and Promised Day is Come.[24]

Other letters included statements on Baháʼí beliefs, history, morality, principles, administration and law. He also wrote obituaries of some distinguished Baháʼís. Many of his letters to individuals and assemblies have been compiled into several books which stand out as significant sources of literature for Baháʼís around the world.[24] The only actual book he ever wrote was God Passes By in 1944 to commemorate the centennial anniversary of the religion. The book, which is in English, is an interpretive history of the first century of the Bábí and Baháʼí Faiths. A shorter Persian language version was also written.[24]

Opposition

[edit]Mírzá Muhammad ʻAlí was ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's half brother and was mentioned by Baháʼu'lláh as having a station "beneath" that of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Muhammad ʻAli later fought ʻAbdu'l-Bahá for leadership and was ultimately excommunicated, along with several others in the Haifa/ʻAkká area who supported him. When Shoghi Effendi was appointed Guardian Muhammad ʻAli tried to revive his claim to leadership, suggesting that Baháʼu'lláh's mention of him in the Kitáb-i-'Ahd amounted to a succession of leadership.

Throughout Shoghi Effendi's life, nearly all remaining family members and descendants of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá were declared by him as covenant-breakers when they didn't abide by Shoghi Effendi's request to cut contact with covenant-breakers, as specified by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[30] Other branches of Baháʼu'lláh's family had already been declared Covenant-breakers in ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Will and Testament. At the time of his death, there were no living descendants of Baháʼu'lláh that remained loyal to him.[31]

Unexpected death

[edit]

Shoghi Effendi's death came unexpectedly in London, on 4 November 1957, as he was travelling to Britain and caught the Asian Flu,[32] during the pandemic which killed two million worldwide, and he is buried there in New Southgate Cemetery.[24] His wife sent the following cable:

Shoghi Effendi beloved of all hearts sacred trust given believers by Master passed away sudden heart attack in sleep following Asiatic flu. Urge believers remain steadfast cling institution Hands lovingly reared recently reinforced emphasized by beloved Guardian. Only oneness heart oneness purpose can befittingly testify loyalty all National Assemblies believers departed Guardian who sacrificed self utterly for service Faith.

— Ruhiyyih[33]

Future hereditary Guardians were envisioned in the Baháʼí scripture by appointment from one to the next. Each Guardian was to be appointed by the previous from among the male descendants of Baháʼu'lláh, preferably according to primogeniture.[31] The appointment was to be made during the Guardian's lifetime and clearly assented to by a group of Hands of the Cause.[31] At the time of Shoghi Effendi's death, all living male descendants of Baháʼu'lláh had been declared Covenant-breakers by either ʻAbdu'l-Bahá or Shoghi Effendi, leaving no suitable living candidates. This created a severe crisis of leadership.[34] The 27 living Hands gathered in a series of six conclaves (or signed agreements if they were absent) to decide how to navigate the uncharted situation.[35] The Hands of the Cause unanimously voted it was impossible to legitimately recognize and assent to a successor.[36] They made an announcement on 25 November 1957 to assume control of the Faith, certified that Shoghi Effendi had left no will or appointment of successor, said that no appointment could have been made, and elected nine of their members to stay at the Baháʼí World Centre in Haifa to exercise the executive functions of the Guardian (these were known as the Custodians).[35]

Ministry of the Custodians

[edit]In Shoghi Effendi's final message to the Baha'i World, dated October 1957, he named the Hands of the Cause of God, "the Chief Stewards of Baháʼu'lláh's embryonic World Commonwealth."[37] Following the death of Shoghi Effendi, the Baháʼí Faith was temporarily stewarded by the Hands of the Cause, who elected among themselves nine "Custodians" to serve in Haifa as the head of the Faith. They oversaw the transition of the International Baháʼí Council into the Universal House of Justice.[38] This stewardship oversaw the execution of the final years of Shoghi Effendi's ordinances of the ten year crusade (which lasted until 1963) culminating and transitioning to the election and establishment of the Universal House of Justice, at the first Baha'i World Congress in 1963.

As early as January 1959, Mason Remey, one of the custodial Hands, believed that he was the second Guardian and successor to Shoghi Effendi.[39] That summer after a conclave of the Hands in Haifa, Remey abandoned his position and moved to Washington D.C., then soon after announced his claim to absolute leadership, and attracted about 100 followers, mostly in the United States.[40] Remey was excommunicated by a unanimous decision of the remaining 26 Hands. Although initially disturbed, the mainstream Baháʼís paid little attention to his movement within a few years.

Election of the Universal House of Justice

[edit]At the end of the Ten Year Crusade in 1963, the Universal House of Justice was first elected. It was authorized to adjudicate on situations not covered in scripture. As its first order of business, the Universal House of Justice evaluated the situation caused by the fact that the Guardian had not appointed a successor. It determined that under the circumstances, given the criteria for succession described in the Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, there was no legitimate way for another Guardian to be appointed.[31][41] Therefore, although the Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá leaves provisions for a succession of Guardians, Shoghi Effendi remains the first and last occupant of this office.[42] Bahá'u'lláh envisioned a scenario in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas in which the line of Guardians would be broken prior to the establishment of the Universal House of Justice, and in the interim the Hands of the Cause of God would administer the affairs of the Baha'i community.[43]

Guardianship

[edit]The institution of the 'Guardian' provided a hereditary line of heads of the religion, in many respects similar to the Shia Imamate.[31] Each Guardian was to be appointed by the previous from among the male descendants of Baháʼu'lláh, preferably according to primogeniture.[31] The appointment was to be made during the Guardian's lifetime and clearly assented to by a group of Hands of the Cause.[31] The Guardian would be the head of the Universal House of Justice, and had the authority to expel its members. He would also be responsible for the receipt of Huqúqu'lláh, appoint new Hands of the Cause, provide "authoritative and binding" interpretations of the Baháʼí writings, and excommunicate Covenant-breakers.[31]

The issue of successorship to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was in the minds of early Baháʼís, and although the Universal House of Justice was an institution mentioned by Baháʼu'lláh, the institution of the Guardianship was not clearly introduced until the Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was publicly read after his death.[44]

In the will, Shoghi Effendi found that he had been designated as "the Sign of God, the chosen branch, the Guardian of the Cause of God". He also learned that he had been designated as this when he was still a small child. As Guardian, he was appointed as head of the religion, someone to whom the Baháʼís had to look for guidance.[24]

Shoghi Effendi on the Guardianship

[edit]Building on the foundation that had been established in ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's will, Shoghi Effendi elaborated on the role of the Guardian in several works, including Baháʼí Administration and the World Order of Baháʼu'lláh.[24][31] In those works, he went to great lengths to emphasize that he himself and any future Guardian should never be viewed as equal to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, or regarded as a holy person. He asked Baháʼís not to celebrate his birthday or have his picture on display.[24] In his correspondences, Shoghi Effendi signed his letters to Baháʼís as "brother" and "co-worker," to the extent that even when addressing youth, he referred to himself as "Your True Brother."[45][46]

Shoghi Effendi wrote that the infallibility of his interpretations only extended to matters relating to the Baháʼí Faith and not subjects such as economics and science.[31]

In his writings, Shoghi Effendi delineates a distinct separation of powers between the "twin pillars" of the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice.[47] The roles of the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice are complementary, the former providing authoritative interpretation, and the latter providing flexibility and the authority to adjudicate on "questions that are obscure and matters that are not expressly recorded in the Book."[31][48] Shoghi Effendi went into detail explaining that the institutions are interdependent and had their own specific spheres of jurisdiction.[48] For example, the Guardian could define the sphere of legislative action and request that a particular decision be reconsidered, but could not dictate the constitution, override the decisions, or influence the election of the Universal House of Justice.[49] In explaining the importance of the Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi wrote that without it the World Order of Baháʼu'lláh would be "mutilated."[50][51][52] In its legislation the Universal House of Justice turns to the mass of interpretation left by Shoghi Effendi.[31]

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Shoghi Effendi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Persian pronunciation: [ʃoːˈɣiː efenˈdiː]; Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [ˈʃæwʔi (ʔ)æˈfændi]

- ^ Shoghi Effendi's gravesite column records his birth as 3 March 1896.[1] After its erection, his wife found written evidence that his real birthday was 1 March 1897.[2]

- ^ Effendi is a Turkish title of respect. 'Shoghi Effendi' is roughly equivalent to 'Sir Shoghi'. He often signed letters as simply 'Shoghi'.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Rabbani 1957.

- ^ Giachery 1973, p. 205.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2002). A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Baha'i Faith. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 314.

- ^ Hartz, Paula (2002). Religions of the World. Baha'i Faith (3rd ed.). New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 13.

- ^ a b Momen 2011.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Baha'i Faith. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 315.

- ^ Hartz, Paula (2002). World Religions. Baha'i Faith (3rd ed.). New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 80.

- ^ Hartz, Paula (2009). World Religions. Baha'i Faith (3rd ed.). New York: Infobase. p. 13.

- ^ Hartz, Paula (2009). World Religions. The Baha'i Faith (3rd ed.). New York: Infobase. pp. 79–84.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H (2022). The World of the Baha'i Faith. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 115.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Baha'i Faith. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 316.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H (2022). The World of the Baha'i Faith. New York: Routledge. p. 105.

- ^ a b Bergsmo 1991.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H (2022). The World of the Baha'i Faith. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 79.

- ^ a b Rabbani 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H (2022). The World of the Baha'i Faith. London: Routledge. pp. 105–106.

- ^ Adamson, Hugh C (2007). The A to Z of the Baha'i Faith. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. p. 438.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopaedia od the Baha'i Faith. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 315.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H (2022). The world ofthe Baha’i Faith. New York: Routledge. p. 93.

- ^ Hatcher Martin, William S J. Douglas (1986). The Baha'i Faith. Australia: Harper & Row. p. 62.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Baha'i Faith. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 316.

- ^ Adamson, Hugh C (2009). The A to Z of the Baha'i Faith. Toronto: The Scarecrow Press. pp. 19–21.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H (2022). The World of the Baha'i Faith. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Smith 2000. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFSmith2000 (help)

- ^ Hartz 2009, pp. 78–85. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFHartz2009 (help)

- ^ St. Barbe Baker 1985.

- ^ Smith 2000, pp. 55–56, 102–103. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFSmith2000 (help)

- ^ Weinberg 1991.

- ^ Stockman 2013, pp. 3.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Smith 2000, pp. 169–170. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFSmith2000 (help)

- ^ "Shoghi Effendi, 61, Baha'i Faith Leader". The New York Times. 6 November 1956.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Meizler 2016.

- ^ Johnson 2020, p. xxx.

- ^ a b Johnson 2020, pp. 8–18.

- ^ Momen 2003, §G.2.e.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi. Messages to the Baháʼí World: 1950–1957, p. 127

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Johnson 2020, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Gallagher & Ashcraft 2006, p. 201.

- ^ Marks 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Hejazi 2010.

- ^ Saiedi 2000, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Smith 2000, pp. 356–357. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFSmith2000 (help)

- ^ Effendi 1991.

- ^ Effendi 1974.

- ^ Effendi 1938, p. 148.

- ^ a b Smith 2000, pp. 346–350. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFSmith2000 (help)

- ^ Adamson 2009, pp. 201–208. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFAdamson2009 (help)

- ^ Johnson 2020, p. 4.

- ^ MacEoin 1997.

- ^ Adamson 2007, p. 206. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFAdamson2007 (help)

References

[edit]- Adamson, Hugh C. (2007). Historical dictionary of the Baha'i faith. Historical dictionaries of religions, philosophies, and movements (2nd ed.). Lanham (Md.): Scarecrow Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8108-5096-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Adamson, Hugh (2009). The A to Z of the Baháʼí Faith. The A to Z Guide Series, No. 70. Plymouth, UK: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81-08-6853-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Bergsmo, M., ed. (1991). Studying the Writings of Shoghi Effendi. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0853983361.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1938). "The Administrative Order". The World Order of Baháʼu'lláh. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-231-7.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1974). Baháʼí Administration. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-166-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Effendi, Shoghi (1 April 1991). Your True Brother: Messages to Junior Youth Written. George Ronald. ISBN 978-0853983248.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Etter-Lewis, Gwendolyn; Thomas, Richard, eds. (2006). Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Baha'is in North America, 1898-2000. Wilmette, IL: Baha'i Publishing Trust. ISBN 1-931847-26-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Gallagher, Eugene; Ashcraft, William (2006). Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America: African Diaspora Traditions and Other American Innovations. Vol. 5. Greenwood. ISBN 0275987175.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Giachery, Ugo (1973). Shoghi Effendi: Recollections. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-050-0.

- Hartz, Paula (2009). World Religions: Baha'i Faith (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60413-104-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Hejazi, Hutan (2010). Baha'ism: History, transfiguration, doxa (Ph.D. thesis). hdl:1911/61990.

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Hollinger, Richard (26 November 2021). "Shoghi Effendi Rabbani". The World of the Bahá'í Faith. London: Routledge. pp. 105–116. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-10. ISBN 978-0-429-02777-2. S2CID 244693548.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Hutchison, Sandra Lynn (26 November 2021). "The English-Language Writings of Shoghi Effendi". The World of the Bahá'í Faith. London: Routledge. pp. 117–124. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-11. ISBN 978-0-429-02777-2. S2CID 244687716.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Johnson, Vernon (2020). Baha'is in Exile: An Account of followers of Baha'u'llah outside the mainstream Baha'i religion. Pittsburgh, PA: RoseDog Books. ISBN 978-1-6453-0574-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Khadem, Riaz (1999). Shoghi Effendi in Oxford. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-423-8.

- MacEoin, Denis (1997). "Baha'ism". In Hinnells, John R. (ed.). The Penguin Handbook of the World's Living Religions. London: Penguin Books. pp. 618–643. ISBN 0140514805.

- Meizler, Michael (1 August 2016). "Baha'i Sacred Architecture and the Devolution of Astronomical Significance: Case Studies from Israel and the US". Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Marks, Geoffry W., ed. (1996). Messages from the Universal House of Justice 1963–86. Baha'i Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0877432395.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Momen, Moojan (2003). "The Covenant and Covenant-Breaker". bahai-library.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Momen, Moojan (4 February 2011). "Shoghi Effendi". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Rabbani, Ruhiyyih (9 December 1957). "The passing of Shoghi Effendi".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Rabbani, Ruhiyyih (1988). The Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith. London, UK: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-900125-97-7.

- Rabbani, Ruhiyyih (2000) [1st edition 1969]. The Priceless Pearl (2nd ed.). London, UK: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-1-870989-91-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Saiedi, Nader (2000). Logos and civilization : spirit, history, and order in the writings of Baháʼuʼlláh. Bethesda, Md.: University Press of Maryland. ISBN 1-883053-60-9. OCLC 44774859.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Smith, Peter (2000). "Shoghi Effendi". A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications. pp. 314–318. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Smith, Peter (1 June 2014). "Shoghi Rabbani as 'Abdu'l-Baha's Secretary, 1918–20". Baháʼí Studies Review. 20 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1386/bsr.20.1.39_1. ISSN 1354-8697.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Stockman, Robert (2013). Baháʼí Faith: A Guide For The Perplexed. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4411-8781-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - St. Barbe Baker, Richard (1985) [1970]. My Life, My Trees (2nd ed.). Forres: Findhorn. ISBN 978-0-905249-63-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Taherzadeh, Adib (2000). The Child of the Covenant. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-439-9.

- Volker, Craig (1 September 1990). "Translating the Bahá'í Writings". The Journal of Bahá'í Studies. 2 (3): 67–78. doi:10.31581/jbs-2.3.5(1990). ISSN 2563-755X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Weinberg, Robert, ed. (1991). Your True Brother: Messages to Junior Youth Written by or on Behalf of Shoghi Effendi. Oxford: George Ronald. pp. 8–22. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- "Shoghi Effendi, 61, Baha'i Faith Leader". The New York Times. 6 November 1956.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Hollinger, Richard (2022). "Ch. 8: Shoghi Effendi Rabbani". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 105–116. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-10. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2. S2CID 244693548.

- Hutchison, Sandra Lynn (2022). "Ch. 9: The English-language writings of Shoghi Effendi". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 117–124. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-11. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2. S2CID 244687716.

- Yazdani, Mina (2022). "Ch. 10: The Persian writings of Shoghi Effendi". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 125–133. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-12. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2. S2CID 244687006.

External links

[edit]- Works by Shoghi Effendi at Project Gutenberg

- Shoghi Effendi - resources from bahai.org

- Writings of Shoghi Effendi – authenticated writings in English

- Biography of Shoghi Effendi

- The Guardian: An illustrated chronology of the life of Shoghi Effendi - the Utterance Project

- The Guardian's Resting Place – from the official website of the Baha'is of the UK

- The first documentary film about his life

- Meditations on the Eve of November Fourth – reflections written by Abu'l-Qásim Faizi on the eve of Shoghi Effendi's passing